Temperature classes are part of a system established by various standards organisations, including the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC), to classify electrical equipment based on its suitability for use in explosive atmospheres.

The classes were designed to mitigate the risk of ignition due to electrical equipment becoming a source of ignition in environments where flammable gases, vapours, or mists are present.

It is crucial for industries to adhere to these temperature classes and ensure that the equipment used is appropriately rated for the specific hazardous area in which it operates. As to the temperature classes themselves, they are specifications that indicate the maximum surface temperature a piece of equipment can reach.

What about dust?

For environments with combustible dust, the classification system is adapted to address the specific risks posed by dust particles.

Unlike gases and vapors, where temperature classes (T1 to T6) are used, for dust, the focus is on the actual maximum surface temperature of equipment relative to the ignition temperature of the specific type of dust present.

The Mythconception

Mythconception is not a real word other than as a descriptive portmanteau to make a valuable point. Let’s get this confusion settled and out of the way—there are other things to learn and know!

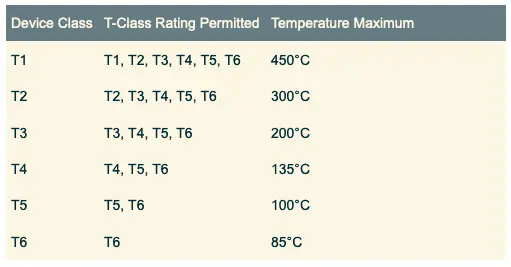

As you can see in the accompanying image there are 6 ratings numbered T1 through T6 that describe the operating temperature of assorted commercial equipment. People have come to the mistaken conclusion that something rated T1 is explosion-proof up to a temperature of 450℃, which it most certainly is not!

T1 only means that the equipment may reach a maximum temperature of 450℃ while operating. This tells the owner and workers that you cannot have an explosion hazard near this equipment that is sensitive to that temperature or less. T1 is not better than T2—it is, in fact, hotter than T2 while operating.

Simply put, T6 is “the best” since very few things are vulnerable to ignition at just 85℃… T6 would be safest compared to any value above it from T5 to T1… Making sure you know that low numbers are worse than high numbers will allow you to avoid a lot of problems. In practice, you should focus on selecting the appropriate temperature class that is both available and safe for use, with T4 and T3 being the most prevalent choices in industry.

[Table] Temperature Classes & Max. Temperatures

| Device Class | Temperature Maximum |

|---|---|

| T1 | 450°C |

| T2 | 300°C |

| T3 | 200°C |

| T4 | 135°C |

| T5 | 100°C |

| T6 | 85°C |

Practical Examples

Taken a step further, paper will ignite at 450℃ , so placing a newspaper or a book on a T1-rated device would likely lead to a fire.

Though not smart, putting a newspaper on a T2-rated device would be relatively safe in comparison. It might char and discolour, but it wouldn’t burst into flame.

Please be aware that, in the context of dust, the 450℃ figure represents an exact maximum surface temperature, rather than a temperature class.

Substances like CS2 (Carbon Disulphide) or C2H5NO3 (Ethyl Nitrate) are combustible between 90 and 102℃ and so would require a T6-rated piece of equipment in their vicinity. Substances like Ammonia (NH3) or Methane (CH4), which are fine with T1-rated equipment, would also be fine with T6 equipment.

The reverse is not true. Both Carbon Disulphide and Ethyl Nitrate would be in significant danger even near class T5, let alone T4 or anything above that. The larger the number, the safer you are likely to be… With that having been said, let’s look at some other important items about these temperature classes.

Why Do We Use the T-Scale?

In addition to the Minimum Ignition Energy (MIE), which was discussed in previous articles, two other properties of inflammable substances must be considered. These are their Flashpoints and their Auto-Ignition Temperatures (AIT).

Under the ATEX directives, the term “Minimum Ignition Temperature” (MIT) is frequently used. It’s important to note that MIT and AIT refer to the same concept.

Flashpoint

The flashpoint of a substance is the minimum temperature at which it can ignite and produce a momentary flame or flash. However, at the flashpoint, the substance does not sustain combustion.

This is just a measure of how easily a substance can vaporise and form an ignitable mixture in the air near its surface. As soon as the triggering source is removed, combustion stops.

Auto-Ignition Temperature (AIT/MIT)

The AIT, on the other hand, is the lowest temperature at which a substance can spontaneously ignite without an external ignition source (e.g. an open flame or spark).

In other words, it’s the temperature at which the substance can start burning on its own due to the existing heat in its environment. Unlike the flashpoint, the auto-ignition temperature leads to sustained combustion.

The flashpoint is important since, while not self-sustaining, in the right (wrong) conditions, it can serve as the ignition source for some other combustible mixture, whether gaseous or suspended dust. It could tip the balance of something near its nominal AIT, triggering a much bigger event.

Additional Complications: Ambient Temperatures

Let’s say, for example, that you have a motor that is rated at Ta + 70℃. What does that mean? Many devices put it much more plainly and say “This device will operate at 70℃ above ambient temperature (Ta)”.

If your workplace is normally 21℃, this means the operating temperature of this device will be 21 + 70 = 91℃. In a hotter environment, say 30℃, its operating temperature is now 30 + 70, or 100℃, pushing you dangerously close to the AIT of carbon disulphide (102℃).

So, not only do you have to consider the substance and its vulnerabilities, but also how the environment itself can change the likelihood of a triggering event.

T-Rated Equipment

For creating a rating for equipment, manufactures use a scale based on temperatures ranging from -20℃ to 40℃ for the ambient air temperature. This means that rated-equipment with a T3 rating will not exceed 200℃ if the ambient temperature is in that range, and the same for all the other readings on the scale. Once you go beyond the “assumed” ambient range you have to start calculating and making sure you’re still safe.

The T-Rating for Atmospheres

If the atmosphere is rated safe for T4 equipment (135℃), then T4, T5, and T6 equipment would be perfectly acceptable, but T3, T2, or T1 would be impermissible and dangerous.

The atmospheric ratings are affected by physical conditions. For example, homogeneous gases have fairly reliable ranges. Butane has an AIT of 287℃, hydrogen is 500, and Carbon Monoxide is 605, but dusts are different.

Dusts in suspension are different than a layer of the same material. It’s counterintuitive to most people, but layers have a lower smoldering temperature than a dust cloud! Cellulose and flour are 490℃ in a cloud, whereas layers will combust at just 430℃. Cocoa is even more dramatic requiring 500℃ suspended, but only 200℃ when in a layer of 5mm. As the layer thickens, heat loss becomes more difficult, further reducing the air/material temperature.

[Table Atmosphere ratings and T-Ratings]

| Atmosphere Rating | T-Class Rating Permitted |

|---|---|

| T1 | T1 T2 T3 T4 T5 T6 |

| T2 | T2 T3 T4 T5 T6 |

| T3 | T3 T4 T5 T6 |

| T4 | T4 T5 T6 |

| T5 | T5 T6 |

| T6 | T6 |

Further Considerations

A small concussive event might seem harmless, but it could dislodge accumulated material on a beam or false ceiling. Such a falling cloud could be too thick and dense to reach its AIT, but the unrealised danger is that large particles fall faster than small particles.

The smaller the particle, the easier it is for it to ignite and combust. The decreasing cloud density may reach its critical threshold and propagate the flaming wavefront of an explosion! This is not the time to laugh at the employee half buried in dust—it’s time to run. You wouldn’t stand around if a propane tank started to spray fuel from a faulty valve.

Housekeeping & smoldering dust layers

Prevention is the best way to avoid many problems. Combined with mitigation strategies to prevent accumulations in the first place, regular tidying, and vacuum or mechanical removal (not pressurised air!) during the processes, is a key to safety.

A motor covered in dust may cause the dust layer to smolder.

Subsequently, this layer could begin to glow, potentially becoming an ignition point for a dust explosion.

Effective housekeeping measures, aimed at preventing accumulation beyond 5mm, are extremely important when mitigating the risk of smoldering.

The Takeaway: what to remember

Knowing what Temperature Classes and T-ratings apply to your atmospheres and equipment, and having policies that are properly followed during purchasing, utilisation, and maintenance will keep your employees, infrastructure, neighbours, and reputation safe.

Remember, for dust groups, we rely on specific temperatures rather than temperature classes to ensure safety.

Should you have any inquiries regarding temperature classes or T-ratings, please don’t hesitate to contact us via phone or email.